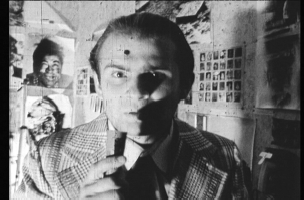

Evgeny Yufit: exploring a Necrorealist Archive

Presenter

Date and time:

Friday, June 14

A screening of works by film-artist Evgeny Yufit in the Darwin Lecture Theatre, University College London, 14 June 2024

Necrorealism was a radical art movement that emerged in the Soviet Union in the mid-1980s. Embracing the absurdist aesthetics of life and necro-acting, the movement explored the liminal zones between life and death, sanity and insanity, Soviet normalcy and apolitical dissidence, the potentiality of black humor and artistic idiocy within and outside the political regime, and the discourses of the late USSR and its everyday reality at a time when, after the death in 1982 of Leonid Brezhnev, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the ‘new’ leaders, to quote Russian philosopher Viktor Mazin, ‘were either already undead or forever dying.’ (Viktor Mazin, ed., Kabinet Nekrorealizma: Iufit: Ъ, Kartina mira series VII, Moscow: Skifiia-print, 2015,

p. 9.) Evgeny Yufit (1961-2016) was the movement’s undeniable leader. In 1985, he founded the independent film studio Mzhalala Film in Leningrad. This united various artists, filmmakers, performers, and regular passers-by, among them Igorʹ Bezrukov, Evgenii ‘The Idiot’ Kondratʹev, Oleg Kotelʹnikov, Andrei ‘The Dead’ Kurmoiartsev, Vladimir Kustov, Ivetta Pomerantseva, and others. The film critic Sergei Dobrotvorskii writes as follows about the films made by the studio:

Early necrorealist declarations affirmed the life of the body abandoned by the soul and advocated pure idiocy, uncorrupted by instinct or the subconscious. Their short films recall Mack Sennett’s slapstick style of the 1910s and the shock aesthetics of the French avant-garde, as well as the unrestrained eccentricity of the Soviet cinema of the 1920s. Characters thickly plastered with zombie clay enact mass brawls, suicides, and monosexual erotic acts. In such strategies, it was easy to discern provocations towards the Soviet myth of social immortality. […] Necrocinema sent back to the empire its most well-worn stereotypes: homosexuality as the flipside of exaggerated masculinity; idiocy as an extreme parody of heroic pathos; and disdain for death, as a natural consequence of collective ethics (Sergei Dobrotvorsky, ‘A tired death’, in A. Miller-Pogacar and J. Nathan, eds., Russian Necrorealism: Shock Therapy for a New Culture [exhibition catalogue], Bowling Green, Ohio: Dorothy Uber Bryan Gallery, 1993, pp. 7–8 (p. 7). )